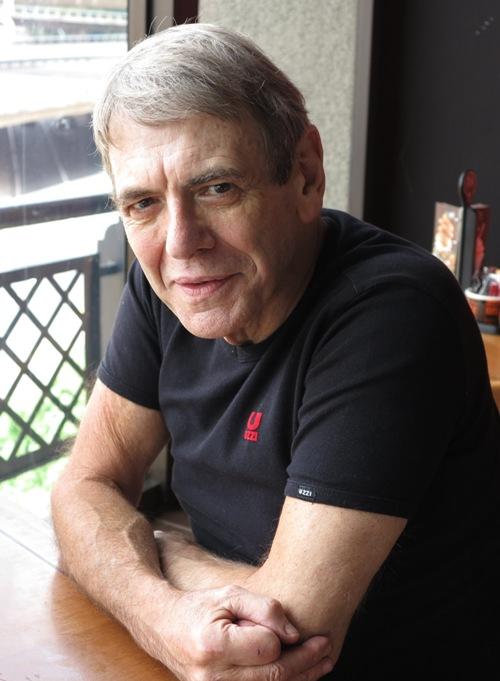

Living in the “city bowl”, Cape Town, and attending St George’s Grammar School at the bottom of the avenue, Stanley Malcolm Knight says growing up couldn’t have been nicer.

Not being the greatest athlete, he made up for it by being an absolute book worm. “There wasn’t a movie that came out that I had not already read the book,” he says. At school he did not have the slightest idea that he would become involved with theatre. “The only thing I did was play the maid in Moliere’s The Mock Doctor in high school. The production was directed by Nina Ferreira, the famous Afrikaans actress and writer.

Stan Knight has worked on over 120 major theatre productions as either lighting designer, scenery constructor or stage manager. The first console he ever worked on was a GrandMaster board at His Majesty’s. What with a huge wheel in the centre and eight clutches to control the banks of dimmers, it was a regular work out running a show. “It was a mother of a board,” he recalls, “but a good learning curve.” A cue took as long as it took and often the operators was still doing Q6 when the stage manager was calling Q7!

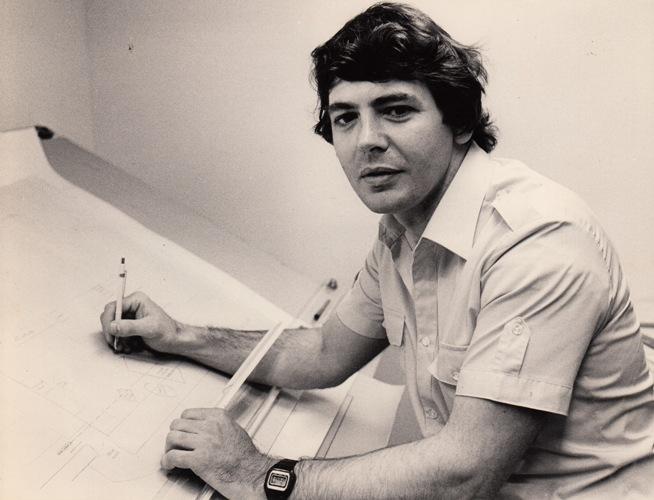

It all began in the late 60’s, when Knight’s girlfriend played the role of the maid in Love from Judy. He found himself meeting up with Jeremy Nichols of Stage Creations, a costume hire company, and before he knew it, he was the stage manager for the show which ran at the Luxurama Theatre. By day, Stan was a computer programmer for the Old Mutual. “I was a very good programmer,” Knight admits and smiles. “I should have made my millions in programming. I was happy.” Knight also worked as a programmer for Toll Gate, the Cape Town bus company. He wrote a huge stock programme which was implemented and used for years after he had left the company.

But an opportunity to work with Brickhill-Burke Productions at His Majesty’s Theatre came up. Knight would earn R90.00 a week. It was pretty good going, because during that period, he bought his first Mini, a brand new deluxe model, for R1 200. He later sold the Mini to travel overseas, and when he returned to South Africa, bought a Toyota Hilux – also for R1 200!

Joan Brickhill (6 March 1924 – 15 January 2014) was a South African actress who worked in radio, theatre, film, and television. Together with her husband, Louis Burke, she founded Brickhill-Burke Productions. When Knight arrived for his first day at the theatre, he was told, “There’s a pile of timber, start building.”

Brickhill-Burke were known for their musical and dance productions tours, which were warmly received throughout the country.

In South Africa those were the Apartheid years. Knight remembers working on Meropa for Brickhill-Burke at the His Majesty’s.

Mondays and Tuesdays were for the black audiences, while Wednesdays to Saturdays for the whites,” he said. “Sunday was for religion. The only good thing was that the system led to a wider audience.”

Knight remembers there was hell to pay when management allowed a coloured dancer to perform in the ‘”Minstrel Scandals”, in black minstrel makeup making him indistinguishable from the rest of the cast! . “We were told to take him out the show and make him a stage hand, but of course he went back on stage for the rest of the tour. He became the principal dancer at the Lido!

Life was very different, and the backstage crew were more of a family. “Working for Brickhill-Burke was a treat,” said Knight. “After a show you were invited to supper at a restaurant, or we went back to the Brickhill’s home to make notes on the show. It was a family, it was fabulous.”

In 1973, Knight went to the New London Theatre with Meropa , (KwaZulu in England). We followed an early production of the musical Joseph, which, Knight recalls, was a “flop.” Their next production was Cats ! Knight had to return to SA to build Gypsy. An English Stage Manager was learning to run the corner, but on the night before the South African production moved to the Piccadilly Theatre, he ran away. Thankfully the SA Company Manager, Marilyn Shrosbree, who had worked the lighting boards on the SA tour, could step in and run the corner . “We would say if you could do the first 8 cues on a manual board, you could run the whole show. The first 8 cues ran in 30 seconds.!” The show played for nearly a year and enjoyed a royal command performance

Knight decided to move back to Cape Town and rejoin Toll Gate. “When I had left, I was the only programmer they had. When I returned, they had replaced me with six others. I loved programming, it was so logical.”

But he had no sooner returned, when he received a phone call from Brickhill-Burke. “Please come up and build Annie.” He, along with Rod Dickson (Joan Brickhill’s nephew), also formed a company called Knight Scene. Rod handled the steel construction while Knight did the sets. The business built scenery for Pieter Toerien , the Academy Theatre and Brickhill-Burke. When His Majesty’s closed (1980), Knight went to work for PACT as a lighting designer, then Drama Production Manager . Later he became Opera Production Manager, before being appointed Head of Workshops. During this time he designed sets and lighting for many of PACT’s productions. He then went to Production Projects as a production manager. Bad times caused Production Projects to retrench staff and Stan went on his own. “By that time I knew enough people with a lot of work. I ended up designing a lot of musicals as well,” he says. Stan has won 7 Vita awards (pre Naledi) for lighting and set design.

“One memorable production was PACT’s Death in Venice in 1994,” says Knight. He remembers that all the costumes were in the white to sepia range, and the only colour used for lighting was chocolate. Productions like the King and I for PACT (1984), used only generic lighting. “You focused 300 instruments for three days, and then you sat down and plotted for three days. It was heavy going. There were no such things as grouping and scenes.

In 2006, Knight went to Russia to light Andrew Botha’s Magic Flute, produced by the Kazan Opera House as their re-opening production. The backlights were 5k Mole moving heads with scrollers. Everything else was Robe. “The only trouble was the new theatre plan included a huge lighting bar in the front of house, but the theatre management refused to have a truss in their beautiful auditorium. But the show ran with success, and toured Holland for 9 weeks doing 43 performances, playing to packed houses. Other highlights include working on the Rocky Horror Picture Show on and off for eight years, Ons vir Jou (4 seasons), Jock of the Bushveld, Shaka Zulu, the RSC version of The Wizard of Oz and his ultimate production, My Fair Lady.

2013 was a quiet year for Knight. When he prepared a talk on lighting incidents in his life and how he worked around certain problems in a theatre environment, he had such valuable input that he was appointed as a lecturer at WITS university for the second year drama students. His passion for the students is fantastic, and you’ll often find him arranging visits at local lighting manufacturing premises to give students input on the way technology is moving forward. In Stan’s life time, this has been a rapid progression. “I remember there was a Pattern 23 fixture that cost R23 and you would think about paying that. Now people want moving lights. A lamp that can change colour and point where you want it to point,” he says. “Now that’s a holiday for lighting designers.”

Knight recently received a phone call asking if he could read music. “I can follow a score,” he said, and ended up stage managing for Opera Africa for the last five years. He will be the Stage Manager for the Mandela Opera, Struggle is my Life, set to take place in June. He is also currently building a baobab tree out of lights for an ‘industrial’, and is happy to be able to donate it to the National Children’s Theatre afterwards.

“I was lucky to get introduced to theatre,” Knight says. “It was fun and it’s still fun.”